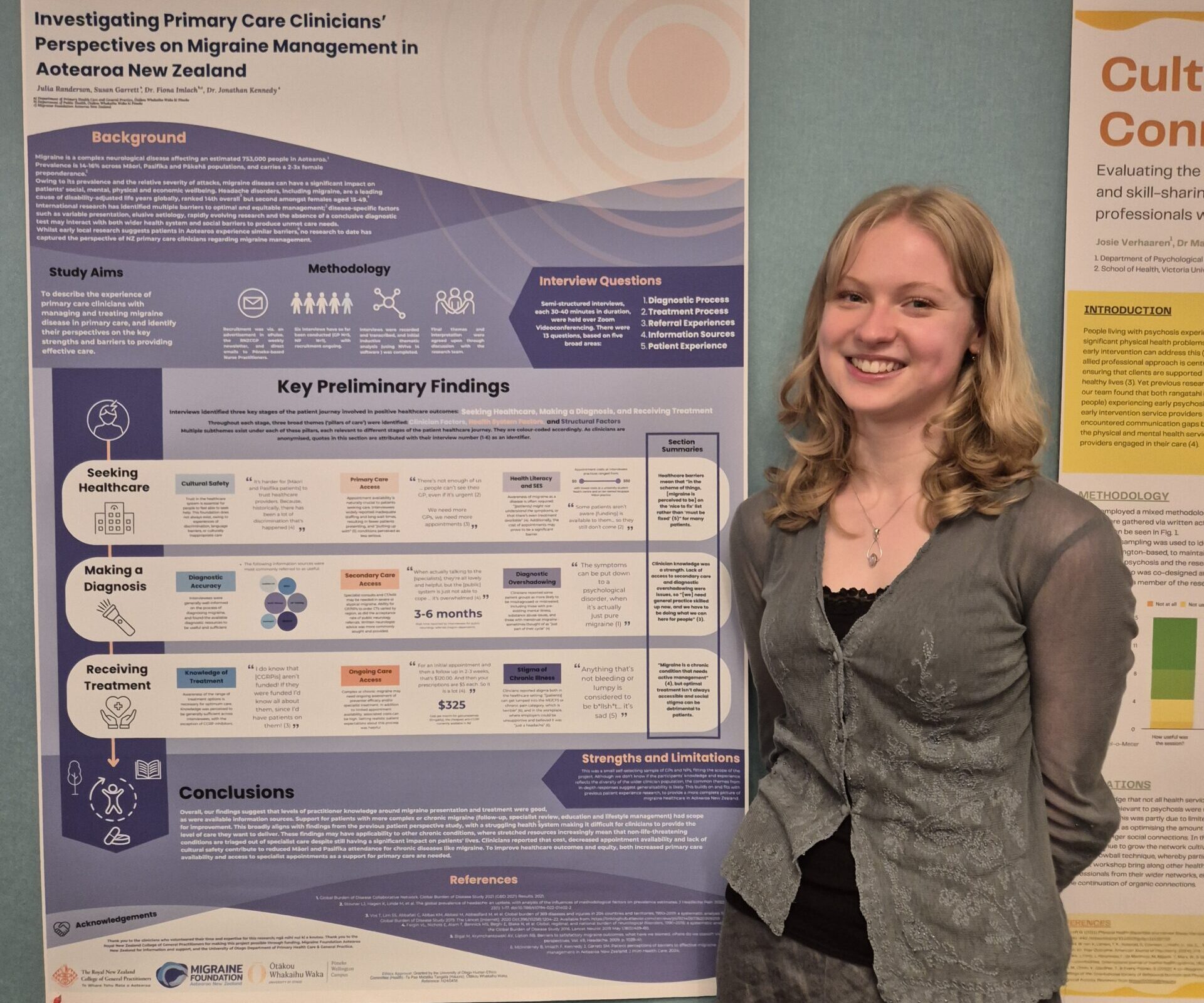

In this guest blog, medical student Julia Randerson shares what she learnt about how migraine is managed in NZ from interviewing primary care clinicians.

Tēnā koutou katoa, Migraine Foundation whānau! My name is Julia, and I’m a fourth-year medical student at the University of Otago, based at the Pōneke campus.

I spent last summer working with Susan Garrett, Dr Fiona Imlach and Dr Jonathan Kennedy on a project funded by the Wellington Faculty of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners and supported by the University of Otago, Wellington (to both of whom I am very grateful).

The project, titled Primary care clinicians’ perspectives on migraine management in Aotearoa New Zealand: a qualitative study, aimed to identify, through a clinical lens, the strengths and weaknesses of current migraine treatment in Aotearoa. This project was a follow-up to work published by last year’s summer student, Blair McInnarney, who explored people with migraine’s experiences in the healthcare system, using data from the Migraine in Aotearoa New Zealand (MiANZ) survey 2022. This time, we sought out the experiences of the clinicians treating migraine, to see where the issues identified did and did not align.

Our research highlighted a few key areas.

Clinician knowledge

Interviewees generally had an excellent level of knowledge on the diagnosis and treatment of migraine, including how varied symptoms and treatment response can be between individuals. There was good knowledge of both acute and preventative medication, as well as addressing environmental/lifestyle factors. Clinicians also described the benefit of allied health professionals, including physiotherapists, health improvement practitioners and vestibular therapists, as well as rongoā Māori treatments such as mirimiri and romiromi.

The in-depth knowledge of the clinicians we interviewed doesn’t necessarily align with the experiences of people with migraine disease. Only a third of people from the MiANZ survey believed their GP’s knowledge of migraine was excellent or very good, and another third wanted to see a neurologist but were unable to. It is likely that it was the more informed GPs who expressed interest in taking part in this study, and indeed, many had personal or family experience of migraine themselves.

What we do know from this research, though, is that up-to-date treatment guidelines are readily available to primary care clinicians if they need to fill knowledge/training gaps, through avenues such as HealthPathways and Best Practice Advisory Centre, and training programmes were generally thorough – all of which is encouraging for enabling higher quality care. Interestingly, part of the reported benefit of a specialist consult was to reinforce and validate the original diagnosis, advice and treatment plans given by the primary care clinician.

Written or phone advice from neurologists was valued greatly by interviewees, although getting an actual appointment for a patient with complex, atypical or refractory migraine was a big challenge. Wait times were months long, and in some parts of the country, referrals to public neurology for migraine disease are always declined. This is due to resource constraints, which also affect secondary care. Some interviewees worried that even written advice from neurologists could become scarce in future, given ongoing staff shortages.

Access to primary care

We know that many people with migraine – even severe/frequent migraine – don’t seek help from healthcare providers. Even when people do present to their doctor, there can be a large ongoing cost from follow-up appointments, especially knowing what a long process finding the right treatment for any individual patient can be!

Interviewees identified lack of primary care access as a major contributor to this problem. Clinicians referenced high cost, lack of funding, staff shortages and long wait times for appointments as causes, and emphasised the need to strengthen primary care in Aotearoa. These factors create barriers for people from low socioeconomic backgrounds in particular, who often could not afford the cost of healthcare, or were unable to get time off work to attend an appointment.

Inequity is a big problem within healthcare access; we know that Māori and Pacific peoples are less likely to be treated for migraine despite experiencing it at about the same rate as Pākehā. The effects of colonisation mean Māori and Pacific peoples have a lower SES on average, creating inequity as described above. They also often experience racism and discrimination in the healthcare system, leading to a lack of trust. Care may also not be culturally safe, and language barriers can get in the way of communicating symptoms/treatment plans.

Finally, interviewees also believed that health literacy (often linked to socioeconomic status) plays a role; some people are unaware of the possibility of treatment, or even what migraine disease is! Again, this was a particular problem for patients with cultural and language barriers, for whom engaging with the health system can be daunting.

Treatment options

Migraine disease is still poorly understood from a pathophysiological basis. Clinicians explained that this means optimal treatment varies significantly between individuals and often requires trial and error, which they acknowledged can be very difficult for patients. Interviewees generally had good resources and knowledge of treatment options, including how to escalate treatment if first-line medications are ineffective.

One challenge identified, though, was a low awareness among clinicians of a new class of migraine treatment, CGRP inhibitors, and thus a low prescribing frequency. As we found out, this was primarily attributed to two factors: firstly, clinicians usually receive information about brand new medications either through specialist initiation, HealthPathways, or when Pharmac notifies the medical community about newly funded drugs. As CGRP inhibitors are not funded and not yet mentioned on HealthPathways, awareness is low. The lack of access to specialist referrals furthers the problem. Secondly, clinicians were concerned that CGRP medications could be prohibitively expensive for many patients (the cost being upward of $300 per month), so were hesitant to prescribe it.

Stigma

Clinicians endorsed the idea of stigma around migraine, which patients reported in the previous research. In particular, they found the public often thought migraine was ‘just a headache’, meaning they had to advocate for patients in work and education settings. They also agreed that certain groups were less likely to be taken seriously, or encounter ‘diagnostic overshadowing’, when reporting their migraine symptoms. Those mentioned included patients with other comorbid chronic illnesses, those with mental health disorders, people with a history of analgesic misuse, and women. Many female GPs, in particular, worried that women were taught to put up with menstrual migraine as ‘just another pre-menstrual symptom’.

Takeaways

Overall, the clinicians interviewed for this paper were informed and dedicated. It was challenging at times to hear about the issues facing migraine treatment in Aotearoa, but simultaneously exciting to discuss possible ways forward. The results indicate many avenues for improvement, from increasing funding to primary and secondary care, to teaching clinicians about cultural safety and challenging internal biases, to increasing community awareness and lowering the cost of medications. Certainly easier said than done, but knowing where to direct advocacy is a great start.

Ngā mihi nui

I would really like to thank Sue, Fiona and Jonathan for being such knowledgeable, passionate and supportive supervisors, and for introducing me to the Migraine Foundation. As someone who came into the project having been newly diagnosed with vestibular migraine, working alongside experts in advocacy for the disease was so inspiring and provided me with a lot of hope for the future of migraine treatment in Aotearoa.

The results of Julia’s research are published here: Primary care clinicians’ perspectives on migraine management in Aotearoa New Zealand: a qualitative study